塔塔集团(Tata Group)的一群专家为印度城市居民开发低收入住房时,其设计者做出了不同寻常的举动——他们挨家挨户查看了要置换的住房。

塔塔房地产(Tata Housing)营销和产品开发主管拉杰卜•达什(Rajeeb Dash)表示:“在贫民区,人们住在一间房子里。但我们看到,他们会在夜里用木板搭建出一个夹层,于是一个150平方英尺的房间一下子就变成了两间,这非常有创意。”塔塔房地产隶属于去年开始销售全球最廉价汽车Nano的印度企业集团塔塔。

塔塔建造的工作室和一居室的价格约为39万至67万卢比(合8400美元至1.45万美元)。从现有住房中寻找灵感的不只是塔塔。国际设计咨询公司Ideo的合伙人弗雷德•杜斯特(Fred Dust)也认为,可以从穷人建造住宅的方式中学到很多东西。他表示:“人们将各种零件组装起来。发掘房屋自身潜力是一个真正体现聪明才智的时刻。”

在建设低收入住房时,规划师、非政府组织和社会企业家没有忽视这种“增量”方法的益处。

在肯尼亚首都内罗毕市非正式定居点胡鲁玛(Huruma)人口密集的Kambi Moto,居民们正受到鼓励自己建房。在一个涉及非政府组织、高等院校、建筑师、城市规划部门和居民自身的创新项目中,各家庭模仿的是一栋三层楼的样板房——他们可以根据自己的承受能力一点点地建造。

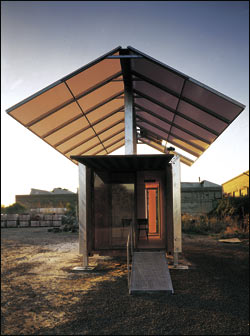

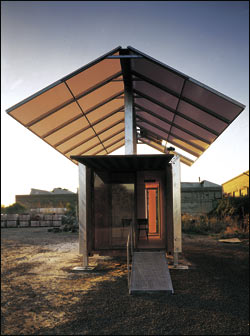

澳大利亚建筑师肖恩•戈德塞尔(Sean Godsell)在“未来小居”(Future Shack)项目中借用了集装箱的设计模式。未来小居是一处为穷人设计的住房,在人道主义灾难期间也可用作临时避难所。这种房屋在任何地方都能轻松地建造起来,其可调节支柱可以适应不平坦的地形,而巨大的斜顶则可以产生太阳能。

在发展中国家难以控制城市无计划的爆炸式增长之际,上述举措受到了人们的密切关注。根据联合国人居署(UN Habitat)的资料,自2000年以来,全球城市人口中新增了5500万贫民区居民——仅比意大利人口总数少几百万。

传统上,只有联合国人居署等机构和Architecture for Humanity等非盈利组织才会想办法为这些人提供住所。然而,私人部门最近已经认识到,为低收入城市客户也具有潜在的商业机遇。

结果,一些创新性的合伙关系开始日渐形成。在哥伦比亚,大型建筑供应公司Colcerámica正与非盈利社会企业家组织Ashoka合作,通过波哥大贫民区Usme的社区领袖,销售一系列低价瓷砖。由于受到信任,社区工人可以进入居民家中,了解希望改善厨房和卫生间的家庭真正想要什么。

Ashoka“人人有房”项目总监瓦莱里娅•布迪尼奇(Valeria Budinich)表示:“企业需要这些市民。对于那些每次给家里建一间房的社区,建材公司的大多数业务团队不了解它们的具体需求。”

与此同时,印度7个邦逾25家私人开发商正在提供低价公寓——根据摩立特(Monitor)为国家住房银行(National Housing Bank)和世界银行(World Bank)进行的一项调查,家庭月收入只须达到7500卢比,就可以买得起最廉价的公寓。

当然,对于许多生活在窝棚区的人来说,即使是塔塔正在开发的此类低价住房也超出了他们的经济承受能力。此外,为处于经济金字塔最底层的人提供住所,所涉及的远不只是优秀的设计和负担能力。实际上,设计住房本身只是所面临的挑战之一。从土地成本和如何确立土地所有权,到如何融资和提供自来水及卫生设施等基本服务,这些挑战涉及方方面面。

例如在巴基斯坦社会企业家塔斯尼姆•西迪基(Tasneem Siddiqui)正在开发的居民社区,创造性不是体现在房屋本身的设计之中——它们只是一排排简单的紧凑型房屋。这个名为Saiban项目的独创性在于房屋融资、营销和购买的方式。

近75%的项目土地以成本价出售给日收入2至4美元的家庭,其余地块则开发成高档住宅在公开市场上出售,为整个项目提供交叉补贴。

一个设计巧妙的筛选过程确保了这些房产将落到真正有需要的人手中——建房期间,潜在买家必须在工地露营。投资于Saiban项目的纽约非盈利风险基金Acumen Fund首席投资官布莱恩•崔尔斯塔德(Brian Trelstad)表示:“在许多低收入住房项目中,人们会转手卖出房产。这种筛选过程把真正想要房子的人和谋求投机的人区分了开来。”

无法获得信贷也是许多贫穷市民面临的一大障碍。出于这个原因,塔塔房地产与Micro Housing Finance Corporation建立了合作关系。塔塔的达什表示:“缺乏购买低收入住房所需的资金,是阻碍此类房屋开发的问题之一。这种合作关系有助于我们弥补这个缺口。”

另一个考虑因素是,贫民区通常也是充满活力的经济中心。麻省理工学院(MIT)城市发展规划教授比什瓦普利亚•桑亚尔(Bishwapriya Sanyal)表示:“许多人有小公司和小型制造企业。因此人们的生活方式与经济上的富足存在密切关联。”

为了复制这种经济可持续性,新的城市社区需要迅速吸引居民,为产品和服务创造需求。不过,人们往往不愿搬家,也不信任开发商。

营销在这里扮演着关键角色。例如,Saiban项目就成立了一个团队,他们的工作就是要让潜在购房人相信,购房者将获得土地所有权,可以信赖开发商。在社区大门旁边的墙上贴着购房合同及相关条款。崔尔斯塔德表示:“因此你的权利一清二楚。这种透明度在微观层面上非常重要。”

译者/君悦

http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001034621

When a group of specialists from Tata Group was developing low-income homes for Indian city dwellers, its designers did something unusual – they went to look at the very houses they sought to replace.

“In the slums, people live in one room,” says Rajeeb Dash, head of marketing and product development at Tata Housing, part of the Indian conglomerate that last year began selling the Nano, the world’s cheapest car. “But we saw that at night they use a wooden platform to create a mezzanine floor, so a 150-square-foot room suddenly becomes two rooms. It is very creative.”

Tata, whose studios and one-bedroom apartments cost Rs390,000-Rs670,000 ($8,400-$14,500), is not alone in turning to existing housing for ideas. Fred Dust, a partner at Ideo, the international design consultancy, agrees that much can be learned from the way poor people build their houses. “There are parts and pieces that get assembled. The organic growth of the home is a real moment of ingenuity,” he says.

The advantages of this “incremental” approach to low-income home creation have not been lost on planners, non-governmental organisations and social entrepreneurs.

In Kambi Moto – a densely crowded section of Huruma, an informal settlement in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi – residents are being encouraged to build their own homes. In an innovative project involving NGOs, universities, architects, the city planning department and the residents themselves, families copy a three-storey demonstration house that can be constructed bit by bit when they can afford it.

Sean Godsell, an Australian architect, turned to the shipping container for his “Future Shack” project – a dwelling for the poor that can also be used as a temporary shelter during humanitarian disasters. It can be easily erected anywhere, its adjustable footing accommodates uneven terrain, and a large pitched roof generates solar power.

As governments in developing countries struggle to manage the explosive, unplanned growth of their cities, initiatives such as these are being closely watched. Across the world, 55m new slum dwellers – only a few million shy of the entire population of Italy – have joined the urban population since 2000, according to UN-Habitat, the United Nations agency for human settlements.

Traditionally, finding ways to house these people has been the preserve of agencies such as UN-Habitat and non-profit groups such as Architecture for Humanity. However, the private sector has recently woken up to the potential business opportunities in serving low-income urban customers.

As a result, some innovative partnerships are emerging. In Colombia, Colcerámica, a large building supplies company, is working with Ashoka, a non-profit network of social entrepreneurs, to market a low-priced line of tiling through local community leaders in Usme, a poor district of the capital, Bogotá. Because they are trusted, the community workers can go into households and find out what families who want to improve their kitchens and bathrooms really require.

“Business needs the citizen sector,” says Valeria Budinich, director of the Housing for All programme at Ashoka. “Most business teams in building material companies have no clue about the specific needs in communities that build homes one room at a time.”

Meanwhile, in India, more than 25 private sector developers in seven states are offering low-cost apartments, the cheapest of which are affordable for households with as little as Rs7,500 in monthly income, according to a study conducted by Monitor Group for the National Housing Bank and the World Bank.

Of course, for many of those living in squatter settlements, even low-cost homes such as those being developed by Tata are beyond their financial reach. Moreover, housing those at the bottom of the economic pyramid involves much more than smart design and affordability. In fact, designing the homes themselves is just one piece in a patchwork of challenges that range from the cost of land and how to establish land ownership to how to finance and put in place essential services such as water supplies and sanitation.

In Pakistan, for example, the creativity of the residential community being developed by Tasneem Siddiqui, a social entrepreneur, lies not in the design of the homes themselves, which are simple compact row houses. The originality of Saiban, as the project is called, emerges in how the homes are financed, marketed and purchased.

Roughly 75 per cent of the plots are sold on a non-profit basis to families earning $2-$4 a day, while the rest are developed as prime residential plots sold on the open market, cross-subsidising the entire development.

A clever filtering process ensures that the properties go to those who need them – potential buyers must camp on the site during construction. “In many low-income housing schemes, people flip the property,” says Brian Trelstad, chief investment officer at Acumen Fund, a New York-based non-profit venture fund that has invested in the Saiban project. “This [the filtering process] differentiates people who want the house from those looking to speculate.”

Access to credit is also a stumbling block for many poor citizens. For this reason, Tata Housing has formed a partnership with Micro Housing Finance Corporation. “One of the issues stalling the development of low-income housing is the lack of finance available to buy such homes. This alliance has helped us address this gap,” says Tata’s Dash.

Another consideration is that slums are often also vibrant economic centres. “A lot of people have small firms and small-scale manufacturing,” says Bishwapriya Sanyal, professor of urban development and planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “So there is a strong connection between how people live and how they survive economically.”

To replicate this economic sustainability, new urban settlements need to attract residents quickly to create demand for products and services. Yet families are often reluctant to move and suspicious of developers.

Here, marketing plays a critical role. A team at Saiban, for example, works to assure potential home buyers they will gain access to the title for the land and that they can trust the developer. Posted on a wall at the entrance gate to the community is the housing contract, with its terms and conditions. “So it’s clear what your rights are,” says Trelstad. “That level of transparency is important at the micro level.”

没有评论:

发表评论