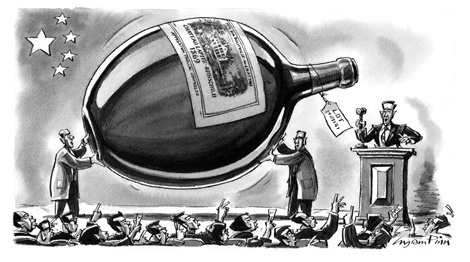

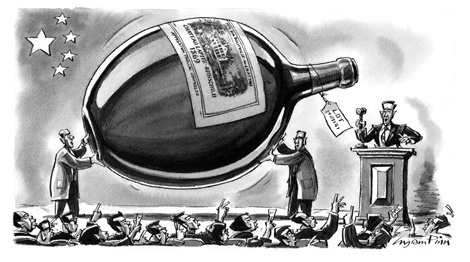

上月早些时候,三瓶1869年份的拉菲堡(Château Lafite)在香港拍出43.79万英镑,这则消息赋予了"中国价格"一层新的含义。这个词通常指的是最低廉的价格——反映出中国制造商的竞争力。但如今在最高端的市场,也存在一个"中国价格",富裕的中国人把稀世奢侈品的价格,哄抬到让许多西方竞价对手吓得脸色发白、以至于悄悄溜出拍卖场的地步。

有些人或许把这视为一个泡沫经济行将破灭的典型征兆。诚然,香港葡萄酒拍卖场上传出的令人屏息的报道,确实让人莫名想起上世纪80年代的情景,当时的日本买家以耸人听闻的价格买下印象派画家的作品——甚至还在食物上撒上金箔。

而另一方面,鉴于欧洲正深陷经济泥潭,上述消息难免让人得出这样一个结论:财富和权力正从西方向东方转移,富裕得让人目眩神迷的亚洲买家争相抢购古老欧洲的珍宝——从地产,到艺术品,再到美酒。如今,全球最来钱的葡萄酒市场在香港,而不是巴黎、伦敦或者纽约。这对价格的影响力震撼人心。

过去十年中,我无意中进行了一次对照实验,让我得以跟踪拉菲堡飞涨的价格。在1855年那次著名的葡萄酒分级中,拉菲等五种佳酿被评为"一级"葡萄酒——最上乘的波尔多红酒。在2000年,我想出了一个好主意,决定给自己的每个孩子购买一箱他们各自出生年份出产的葡萄酒——等他们到了21岁再喝。

我女儿是1993年出生的,这在波尔多可不是个"大年"。来自Farr Vintners的人士建议,这个年份的酒,只有拉菲肯定能够保存21年。即使是当时,拉菲也已经贵得有点吓人了,所以我只买了三大瓶(相当于六瓶),外加六瓶1993年的雄狮庄(Léoville-Las-Cases )。雄狮庄属于二级葡萄酒,比拉菲低了一个档次。上周,我请人给这些酒(目前仍保存在酒窖里)估了价。

十年间,我的三大瓶拉菲增值了大约8倍,而雄狮庄的价格却几乎没有变化。中国买家追捧的是顶级品牌。可是,就连最内行的品酒专家,也尝不出拉菲与价格便宜很多的葡萄酒有何区别。我之所这么肯定,是因为2008年我在达沃斯参加过一次品酒会。

当时,英国《金融时报》的简希丝•罗宾逊(Jancis Robinson)挑选了11款2001年份的葡萄酒,其中5款是顶级波尔多,包括拉菲和拉图尔(Latour),6款是新世界葡萄酒。出席晚宴的人士(主要是有钱的葡萄酒爱好者)"盲品"了所有葡萄酒,然后对它们进行排名。新世界葡萄酒轻松占据了前几名位置,拉菲则"名落孙山"。排名最靠前的波尔多是拉图尔,排在第五位。

但2001年的拉菲目前卖到了一瓶800英镑左右,而在达沃斯品酒会上更胜一筹的葡萄酒——来自澳大利亚的慕斯森林(Moss Wood)解百纳和来自南非的Vergelegen——却只卖43英镑和14英镑。波尔多迷们可能会说,新世界葡萄酒酒劲大、酒味浓,所以在集体品酒中往往能够脱颖而出。我们也可能过早品尝了拉菲。

理性与否姑且不谈,拉菲热显然与这种葡萄酒的味道没有多大关系。假如你是在做慈善,我猜你会说拉菲是个古老而伟大的品牌,而这本身就具有价值,就好比一幅凡高真品肯定比一幅难辨真假的赝品值钱得多。

此外,对有些人来说,贵得吓人的葡萄酒价格非但不会让人却步,反而正是其吸引力所在。假如你要取悦香港的岳父大人或生意伙伴,还有什么比奉上一瓶贵得让人咋舌的葡萄酒更靠谱的呢?

这仍然解释不了为什么拉菲——而不是其它葡萄酒——会成为拍卖场上的明星。部分原因要归功于聪明的营销。拉菲堡在刻意地追逐中国市场。他们近期宣布,2008年份拉菲的标签上将带有中国数字"八"——八在中国被视为吉利数字。有人推测,拉菲之所以在中国受追捧,部分原因在于这个名称比其它一级葡萄酒好念。一箱2009年的拉菲目前售价在1.6万英镑上下,比名称拗口的奥比昂(Haut-Brion)贵出一倍。

对欧洲人来说,在目睹诸多破产事件的当下,中国兴起的葡萄酒热应该值得欢欣鼓舞。拉菲如今成了顶级品牌,而欧洲多的是此类品牌:路易威登(Louis Vuitton)、兰博基尼(Lamborghini)、卢浮(the Louvre)、拉菲。这还只是以字母L开头的品牌。想想看吧,如果我们按照字母表顺序数下去,会有多少欧洲能在亚洲推广的品牌。

当然,有一个情况让人略感汗颜。给拉菲打造一个"中国价格",实际上已使饮用此酒变得近乎不可思议。因此,我可能会卖掉女儿的三大瓶拉菲。这三瓶酒如今的价值相当于大学两个学期的学费。剩下的钱,我可以拿出一部分给她买箱价值170英镑的南非Vergelegen。我听说这酒的味道也一样好。

译者/杨远

http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001035823

The news earlier this month that three bottles of Château Lafite, from the 1869 vintage, had sold at auction in Hong Kong for £437,900 gives a new meaning to the "China price". This phrase usually means the lowest price – reflecting the competitiveness of Chinese manufacturers. But there is also a "China price" at the top end of the market, as rich Chinese bid up the price of rare, luxury goods to levels that make western rivals go pale and slink out of the auction room.

Some might see this as a classic symptom of a bubble economy about to pop. Certainly the breathless reports from today's Hong Kong wine auctions are oddly reminiscent of the late 1980s, when Japanese buyers were paying unheard of prices for Impressionist art – and sprinkling gold leaf on to their food into the bargain.

On the other hand, with Europe in deep economic trouble, it is difficult to avoid drawing an obvious moral about the transfer of wealth and power from west to east, as intoxicatingly rich Asian buyers snap up the treasures of old Europe – from property, to art, to fine wine. Hong Kong – rather than Paris, London or New York – is now the most lucrative wine market in the world, and the impact on prices is spectacular.

Over the past decade I have inadvertently conducted a controlled experiment that has allowed me to track the soaring price of Château Lafite, one of the five wines rated as "first growths" in the famous 1855 classification – the very best of red Bordeaux. In 2000, I decided that it would be a nice idea to buy each of my children a case of wine produced in the year they were born – to be drunk when they turned 21.

My daughter was born in 1993, which was not a great year in Bordeaux. The man from Farr Vintners advised that, from that vintage, only Lafite was certain to last 21 years. Even then, Lafite seemed intimidatingly expensive, so I bought just three magnums (the equivalent of six bottles), topping up the purchase with six bottles of Léoville-Las-Cases (1993) – which is a second growth, just one notch below Lafite. Last week, I asked for a valuation of the wine – which is still sitting in a cellar.

My three magnums had gone up by about 800 per cent in value over a decade. But the price of the Léoville-Las-Cases has barely budged. It is the very top brands that the Chinese buyers are after. And yet even the most dedicated connoisseurs of wine cannot tell the difference between Château Lafite and much cheaper wines. I can say this with certainty, having attended a comparative tasting in Davos in 2008.

Jancis Robinson of the Financial Times had selected 11 wines from 2001 – five were top Bordeaux, including Lafite and Latour. Six were new world wines. The group at the dinner, mainly wealthy wine-lovers, tasted all 11 wines "blind" – and then ranked them. The new world wines came comfortably top. Lafite finished close to last. The top-ranked Bordeaux was Latour, which came in fifth.

But Château Lafite 2001 currently sells for about £800 a bottle; whereas you can still get the wines that tasted better in Davos, Moss Wood cabernet from Australia and Vergelegen from South Africa, for £43 and £14, respectively. Bordeaux fans could argue that new world wines are powerful and alcoholic, so tend to stand out in group tastings. We may also have drunk the Lafite too early.

Rationalisations aside, Lafite-mania clearly has little to do with the taste of the wine. If you were being charitable, I guess you could say that Lafite is a great and ancient name – and that has a value; in the same way that a real Van Gogh is much more valuable than an identical fake.

But it is also clear that for some people, the staggering expense of the wine is an attraction, not a deterrent. If you are trying to impress your father-in-law or a business partner in Hong Kong – what better way than to serve a wine that is known to be mind-numbingly costly?

That still leaves the question of why Château Lafite has become the star of the auction rooms, rather than some other wine. Partly, it is shrewd marketing. The people from Lafite have deliberately gone after the Chinese market. They recently announced that the label for the 2008 vintage would feature a Chinese symbol for the figure eight – which is deemed to be a lucky number. Some speculate that Lafite's popularity in China is partly because it is easier to pronounce than its rival first-growths. A case of Lafite (2009) currently goes for about £16,000 – double the price of the unpronounceable Haut-Brion.

For Europeans, staring bankruptcy in the face, China's wine mania should be encouraging. Lafite is now a premium brand and Europe has plenty of those: Louis Vuitton, Lamborghini, the Louvre, Lafite. And that is just the letter L! Think of all the brands Europe can market in Asia, once we start working our way through the alphabet systematically.

Of course, there is something slightly humbling about the fact that the creation of a "China price" for Lafite has made actually drinking the wine almost unthinkable. I will probably sell my daughter's three magnums of Lafite – which are now worth the equivalent of two terms' university fees. I could use some of the balance to buy her a case of Vergelegen for £170. I've heard it's just as good.

没有评论:

发表评论