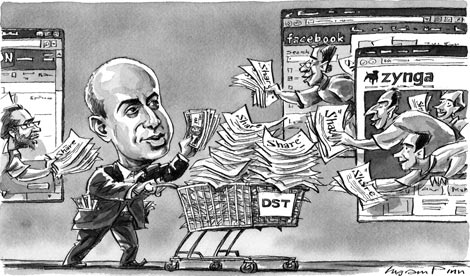

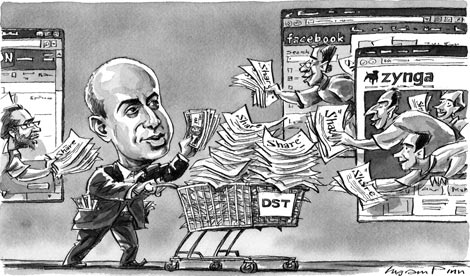

尤里•米尔纳(Yuri Milner)在互联网企业家圈子里非常受欢迎。Facebook创始人马克•扎克伯格(Mark Zuckerberg)邀请他去做客,网游公司Zynga首席执行官马克•平卡斯(Mark Pincus)把他看作值得信赖的顾问。硅谷风险投资家对他的感情则明显冷淡得多。

“他趁所有人都熟睡时发动夜袭,你也许会对他利用时机的大胆和机敏赞赏不已,但现在我们醒了,他不可能再这样做了,”硅谷一位资深投资者这样评价米尔纳。米尔纳是本月在伦敦上市的俄罗斯互联网公司Mail.ru的董事长,也是Mail.ru的投资方——俄罗斯数字天空技术(Digital Sky Technologies,简称:DST)的首席执行官。

首次公开发行(IPO)的严重匮乏让风险投资基金和高科技公司均苦不堪言,面对这种局面,米尔纳想出了一个解决办法:他为这些公司提供一条便捷途径,无需上市,就既可以追加资本,也能让它们的员工出售所持股份。

他的远见让DST以现在看来极其低廉的价格,购入Facebook近10%的股份,以及Zynga和Groupon的部分股份——后两者都属于最优质的互联网企业。他撼动了后期科技投资,让硅谷的精英们大感受挫。

问题在于,他是否是第二个孙正义(Masayoshi Son)——孙正义是日本软银集团(SoftBank)掌门人,因上世纪90年代入股雅虎(Yahoo)及其它企业而声名鹊起,但在互联网泡沫破灭时遭遇滑铁卢。或者说,他是一位创新者,永远地改变了投资者与企业家之间的实力平衡?

在我看来,尽管米尔纳的成功在一定程度上要归功于市场的周期性,还有一部分原因是他占据了先发优势——社交媒体的繁荣催生出一些高估值、增长迅速的公司,它们希望尽可能长久地保持私有,而米尔纳在金融危机过后灵敏地捕捉到了它们——但其影响将是长期存在的。

让风险投资基金恼火(上述资深投资者说道:“你可以从我的声音里听出沮丧。”)的一个原因在于,米尔纳没有像以往的外国投资者那样,试图打入硅谷或好莱坞,当一个“更大的笨蛋”,做出最烂的交易。相反,他比所有那些自吹自擂要打造出第二个苹果(Apple)或谷歌(Google)的人都要技高一筹。

米尔纳的诀窍是发现了一点,正如上周他在摩纳哥媒体论坛(Monaco Media Forum)上对我说的:“企业创始人会拥有感召力,并洞察未来,但一些人只希望付房贷,过平常人的生活。”换言之,像扎克伯格之类有远见卓识的人,甘愿只做个纸上亿万富翁,住在租来的房子里,而员工们希望脱手股份。

米尔纳去年5月向Facebook开出了一个条件:他向Facebook投资2亿美元现金,以换取后者2%的股权(意味着该公司的估值达到100亿美元),且公司正式批准让他以较低估价从员工收购股份。他没有要求获得董事会席位,而甘当“仆人”,让扎克伯格继续按照自己的意愿管理公司。

相比其它人的条件,100亿美元的估值和不要管理权这两个条件要优厚太多,但现在看来,这些条件极其划算——Facebook目前估值达到400亿美元。“如果你选出最优秀的两、三家高速发展的企业,比其他任何人的报价都高出个20%,再开出一些更优惠的条件,你就成了一个天才,”一位资深投资者如此表示。

复制这些早期的成功存在明显的难题。一个就是像Facebook和Zyngas这样的企业太少了——依照米尔纳的模式,他要物色的是那些正迈向巨额IPO、但想要坚持一段时间的高增长公司。他自己估计,全球仅有25家这样的顶尖企业,而他不是唯一的猎手。

第二个困难是,这种操作的风险比米尔纳迄今对外表露的要大。除了对谷歌这样的顶尖科技公司外,IPO市场已冷清了多年,而企业往往以低于风投估值的价格卖掉。社交媒体公司Slide在2008年的一项风投交易中估值达到5亿美元,但谷歌今年夏季只花了2.3亿美元就收购了它。

“一些企业早先以较高估值获得了融资,它们不希望上市,以免股权遭大幅稀释,”普华永道(PwC)合伙人特雷西•莱弗特洛夫(Tracy Lefteroff)表示。当米尔纳作为——用哈佛(Harvard)教授乔什•勒纳(Josh Lerner)的话讲——“时代的特征”而载入史册时,对二级企业开出效仿他的条件的投资者可能会蒙受损失。

但我怀疑硅谷的投资者能否那么容易地摆脱他。企业家与投资者之间关系紧张由来已久,一些公司的创始人在投资者推动撤资时,都蒙受了一定的损失。米尔纳指出,谷歌的最高估值是其IPO价格的10倍,Ebay和雅虎分别为78倍和126倍。

迄今为止,这些精英企业的创始人难以抗拒风险投资基金的意愿,但米尔纳开创的交易——Elevation Partners最近向Yelp提供投资时已模仿了这一套路——给了这些企业更大的话语权。这些交易让员工满意,还让企业家保留管理权。

这也许让早期的投资者怨恨不已——他们既投入资金,还提供宝贵的运作诀窍,结果却在后期让一个俄罗斯投机商人抢了先。米尔纳已打入这个圈子,而别人很难再把他赶出去。

译者/陈云飞

http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001035714

Yuri Milner is very popular among internet entrepreneurs. Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, encourages him to drop by and Mark Pincus, chief executive of Zynga, an online games company, regards him as a trusted adviser. Among Silicon Valley’s venture capitalists, feelings are decidedly cooler.

“He came on a night attack when everyone was asleep and while you might be full of admiration for his audacity and cunning in taking advantage of that moment, we’ve woken up now and he won’t be able to do it again,” says one Valley investing veteran about Mr Milner, chairman of Mail.ru, a Russian internet company that floated in London this month.

Mr Milner, who runs Digital Sky Technologies, the investment fund of Mail.ru, came up with a solution to the initial public offering drought that has afflicted venture capital funds and technology companies. He offers them a simple way to raise fresh money, and for their employees to sell shares, without going public.

His insight enabled DST to

acquire nearly 10 per cent of Facebook and stakes in Zynga and Groupon, both premier league internet properties, at prices that are now bargains. He has shaken up late-stage technology investing and bruised the Valley’s elite.

The question is whether he is another Masayoshi Son of Softbank, the Japanese investor who rose to fame by acquiring stakes in Yahoo and other properties in the 1990s but flamed out in the dotcom crash, or an innovator who has changed the balance of power between investors and entrepreneurs for good.

My feeling is that, although Mr Milner’s coup was partly cyclical and partly a matter of first-mover advantage – the social media boom has produced some highly valued, fast-growing companies that want to remain private for as long as they can and he picked them adroitly in the wake of the financial crisis – it will have a long-term impact.

One reason for the VCs’ irritation (“You can hear the frustration in my voice,” says the veteran investor) is that Mr Milner has avoided playing the traditional role of a foreign investor who tries to break into Silicon Valley or Hollywood – that of the greater fool who takes the worst deal. Instead, he outmanoeuvred those who pride themselves on building the next Apple or Google.

Mr Milner’s trick was to spot that, as he told me last week at the Monaco Media Forum: “The company founder is charismatic and sees the future but some people just want to pay their mortgages and live a normal life.” In other words, visionaries such as Mr Zuckerberg are happy to be billionaires on paper and live in rented houses, while employees want to cash out.

Mr Milner responded by offering Facebook a deal in May last year: he would inject $200m in cash in return for a 2 per cent stake valuing the company at $10bn, and official approval to tender for the shares of employees at a lower valuation. He did not demand a seat on the board and was content to be “a servant” – to let Mr Zuckerberg keep on running things as he wished.

Both the $10bn valuation and the lack of control rights were much better than rival offers, but they have so far worked out extremely well – Facebook is now valued at $40bn. “If you select the best two or three high-velocity companies, pay 20 per cent more than anyone else and offer softer terms, you look like a genius,” says one venture investor.

There are obvious problems with replicating these early successes. One is that there are only a limited number of Facebooks and Zyngas around – his formula requires him to find high-growth companies that are heading for multi-billion dollar IPOs yet want time. He himself estimates that there are only 25 of these choice properties in the world, and he is not the only hunter out there.

A second difficulty is that it is a riskier business than Mr Milner has made it look so far. The IPO market for all but outstanding tech companies such as Google has been slow for years and companies often sell for less than venture valuations. Slide, a social media company, was valued at $500m in a 2008 venture deal but Google bought it for only $230m this summer.

“Some companies have raised money at huge valuations in early rounds and don’t want to go public and suffer huge dilutions,” says Tracy Lefteroff, a partner of PwC. Investors that match Mr Milner’s terms on second-tier properties could get burned while he goes down in history as, as Josh Lerner, a Harvard professor, puts it, “an idiosyncratic reflection of the times”.

But I doubt whether it will be that easy for Silicon Valley’s investors to get rid of him. Tensions between entrepreneurs and investors are as old as the hills and the founders of some companies left money on the table when investors pushed to exit. Mr Milner points out that, at their peak valuations, Google was worth 10 times, Ebay 78 times and Yahoo 126 times the IPO price.

Until now, the founders of such elite enterprises have struggled to resist the wishes of venture funds, but the deals pioneered by Mr Milner – and already mimicked by Elevation Partners in a recent financing of Yelp – give them greater power. They can keep employees happy while retaining control.

This may gall early-stage investors who have invested both money and precious expertise only to have a late-stage Russian bargain hunter outbid them, but that’s life. Mr Milner has broken into the club and he will be hard to dislodge.

没有评论:

发表评论